Update (31 March 2020): We have decided to also postpone our three May workshops. We plan to re-schedule all of our events for the autumn.

Update (14 March 2020): Following careful consideration of the current COVID-19 pandemic, we have decided to postpone our March workshops. We will evaluate whether our May events can go ahead in due course. Please check back for updates and we hope to see you on a future date!

We invite you to a workshop where all will have a chance to participate in a conversation about infertility, fertility treatment, scientific knowledge, embryo/medical imaging and patient decision-making. You will have the opportunity to hear more about our ongoing research in the area.

There will be snacks and drinks and lots of space for sharing ideas, opinions and experiences.

The workshop will take place in London on five dates across March and May 2020. For more information and to book your place, follow the links to our eventbrite pages:

CANCELLED 14 March 2020. Timber Lodge café, 1A, Timber Lodge Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, Honour Lea Ave, London E20 1DY. Starts at 2.30pm. SIGN UP HERE.

CANCELLED 17 March 2020. The Vagina Museum, Unit 7&18 Stables Market, Chalk Farm Road, London, NW1 8AH. Starts at 6.30pm. SIGN UP HERE.

CANCELLED 13 May 2020. Yurt café, St. Katharine’s Precinct, 2 Butcher Row, London E14 8DS. Starts at 6.30pm. SIGN UP HERE.

CANCELLED 16 May 2020. Poplar Union, E5 Roasthouse, 2 Cotall St, Poplar, London E14 6TL. Starts at 2.30pm. SIGN UP HERE.

CANCELLED 28 May 2020. The Canvas: Café & Creative Venue, 42 Hanbury St, Spitalfields, London E1 5JL. Starts at 6.30pm. SIGN UP HERE.

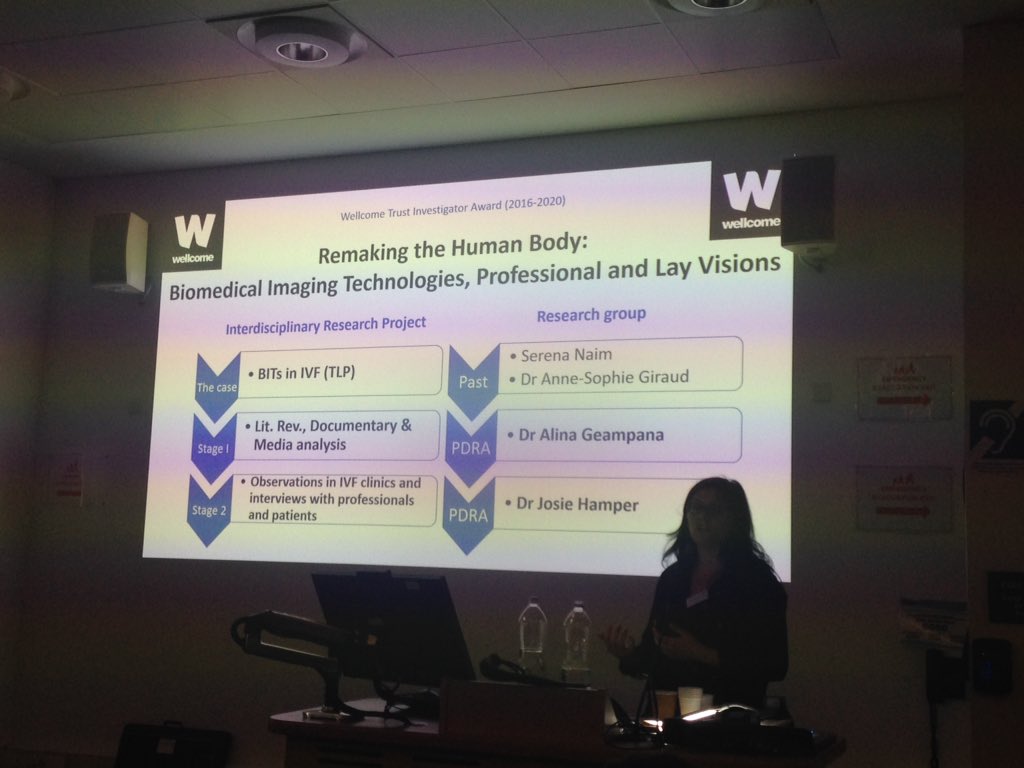

These events are funded by the Wellcome Trust and supported by Fertility Network UK.