The first RHB article is now out in Social Science & Medicine! The publication, entitled “The trouble with IVF and randomised control trials: Professional legitimation narratives on time-lapse imaging and evidence-informed care,” highlights how IVF professionals navigate the complex landscape of add-ons and evidence when it comes to using time-lapse imaging in embryology labs across the UK. Drawing from our interview data, we show that clinic staff see several benefits in the use of imaging technologies. These benefits are diverse and not always captured in current public conversations on add-ons. The main contribution of the article is to highlight how professionals think about the benefits of time-lapse more widely. In light of our findings, we suggest that it is worth thinking about a more nuanced understanding of evidence-based-medicine as it relates to the IVF sector specifically. Read the full (open access) article here: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113115

Author: Alina Geampana

The RHB team had a productive summer with amazing conferences and manuscript writing. Having received so much useful feedback as of late, we are ready to publish some of the first project findings. The conferences we attended in the past months have really helped us contextualize our research and hone our arguments.

In August, RHB was at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, where we were part of one of the five (!) Sociology of Reproduction panels. Given that RHB is UK-based, we were able to assess how the issues raised in our research relate to wider concerns regarding technology, medicine, and reproduction. Although the UK IVF conversation has lately involved a sustained critique of commercialisation, audiences have remarked that the industry here is quite tightly regulated when compared to other countries (the U.S. especially), where healthcare is largely driven by a strong consumer logic. This is particularly true of fertility treatment, where multiple IVF cycles can cost tens of thousands of US dollars. As reproduction researchers, however, we strongly feel that fertility care should be an integral part of public healthcare services for all.

The ethics of new biomedical technologies was the focus of the first of our two panels at the 4S (Society for Social Studies of Science) meeting in late summer. Here, scholars raised excellent questions about the introduction of new medical technologies and the value they add to practice. As we have grappled with the role of time-lapse in IVF, we have found that the meanings of this technology can be different depending on one’s position and perspective. For example, time-lapse can be a great lab tool for embryologists, while also a reassuring technology for patients who want to know that their embryos are kept in a stable environment 24/7. This is an aspect of time-lapse that our audience has found incredibly interesting.

We have also recognized in our presentations that efficiency evidence is currently an important criteria for assessing new IVF technologies, especially in the UK add-on conversation. Based on our findings so far, this is one of the most salient themes that arises when talking to professionals about the value of new treatments. In the near future, we aim to publish our data on how fertility professionals in the NHS conceptualise evidence and its relation to time-lapse tools. In the meantime, we are also working on finishing up data collection, so that we can share findings on patient perspectives as well in the coming year. Last but not least, planning for public engagement activities in underway, with several events that will take place in 2020. Stay tuned!

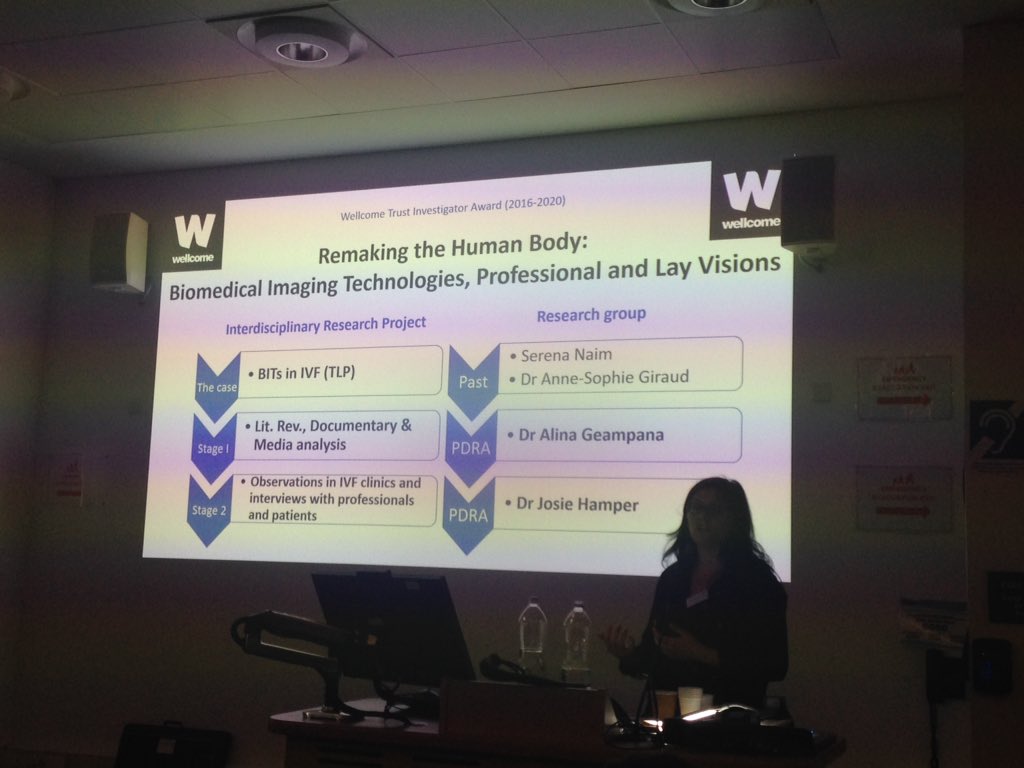

Last week we were delighted to attend the BSA Human Reproduction Study Group Annual Conference, held on June 12 at De Montfort University (DMU) in Leicester. During one of the late afternoon sessions, Manuela Perrotta (pictured below) presented our paper-in-progress on professional attitudes towards the role of evidence-based-medicine (EBM) in IVF. The presentation emphasized the case of time-lapse and the role EBM has played in its uptake. The conference included a thought-provoking plenary from Prof. Marcia Inhorn as well as excellent panels on gamete donation, reproductive genetics, donor conception, reproductive timing, and abortion. Many thanks to the Centre for Reproduction Research at DMU and convenors Dr Kylie Baldwin and Dr Cathy Herbrand for the warm welcome.

We go to many exciting conferences and events throughout the year. Fertility Fest, however, is very special in that it bridges the gap between art and science, lay and professional. Infertility as a topic of discussion stirs intense emotions and Fertility Fest provides a very much needed outlet to express such feelings and have conversations about them. Eager to immerse myself in this year’s festival, I attended the Big Fat Festival Day this May. I must also mention here that the 2019 venue, The Barbican Centre, was a fabulous fit and contributed to the convivial atmosphere of the festival.

When it comes to infertility and IVF treatment, some topics come up more often than others. As such, I would like to focus on the conversations that stood out for me this year – the conversations that, I thought, were novel and really made me think about some of the more painful and uncomfortable questions. For example, what happens when IVF treatment doesn’t work? When our hopes and dreams disintegrate? How does one re-evaluate their life and choices? How does one grieve? And is there meaning to life beyond having children?

During the opening session, Lisa Faulkner talked about her personal journey and the decision to adopt. Her experience really conveyed the difficult choices one has to make after several failed rounds of IVF. This issue seems poignant to me, yet seldom discussed. How does one know when to say no when we put so much emphasis on hope and being positive? Lisa talked about her initial reluctance towards adoption – something that I found refreshing. There are too many people who assume that adopting should be an easy decision for infertile couples, when, in fact, it is not. It was apparent to me that we need to have more conversations about adoption, who it’s for and who it isn’t for.

The Invisible Man was the morning panel that piqued my interest (but, trust me, it was very hard to choose). The focus on men made me reflect on the tough situations that are particular to the male experience of infertility. Elis Matthews talked about being diagnosed with azoospermia and struggling with identity, faith and the meaning of life. The devastation of hearing the word ‘zero’ (sperm) from a doctor really drove home how insensitive some medical encounters can be. Elis, however, admiringly managed to find humour in the situation. Men talked more generally about having to deal with tough questions about meaning and fulfilment – questions that they had to confront because of their experience with infertility. As a woman, I was moved to hear actor and writer Rod Silvers talk about feeling that he had failed his partner when he found out he might not be able to ‘provide’ her with biological children. I wondered if we really understand what infertility means for a couple as a unit, not just individually.

The highlight of the day, for me, however, was the premiere of Irina Vodar’s documentary Anything You Lose: a movie that intimately captures her infertility journey over 7 years. The camera follows Irina and her husband to multiple clinics, documenting their pursuit of parenthood. Heartbreaking moments of disappointment invite the viewer to reflect on the emotional toll that infertility takes on couples. Echoing the questions I outlined above, Irina’s story forces her and the audience to ponder the meaning of life without children and what we do when things don’t go the way we planned. What I appreciated most about Anything You Lose it that it doesn’t fall into Hollywood clichés about infertility. It doesn’t gloss over the complex medical procedures and decisions that patients have to make. It also shows the toll that infertility can take on relationships and the raw emotions it brings out of people. I came out of the Barbican Centre with many things to think about. In fact, I am still pondering questions as I’m writing this post.

Thank you Fertility Fest for another great year!

One of our most anticipated events this year was the British Sociological Association (BSA) meeting, held between April 23 and 26 at Glasgow Caledonian University. Manuela Perrotta presented new findings from our project, focusing on the role of evidence-based medicine (EBM) in IVF. Our paper analysed professional attitudes towards time-lapse imaging technologies and how they illustrate a very ambiguous and complex relationship between reproductive medicine and EBM. We did not miss our chance to catch up with current research in our field and attended several medical sociology and STS (Science and Technology Studies) streams. Moreover, the team enjoyed excellent plenaries, including Nonna Mayer on voting and social precariousness and Satnam Virdee on race, otherness, and modernity. BSA 2019 provided excellent content and food for thought. We are excited to see what the next year brings.

Qualitative health researchers are well aware that we work in a world dominated by big data, quantitative research, and the gold standard of randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Upon hearing about a conference focused not only on contemporary health issues, but also on qualitative methods, the RHB team jumped at the chance to participate. Not unexpectedly, we are very glad we did.

The QHRN 2019 conference held last week on March 21-22 in London highlighted the diversity and richness of qualitative methods used by attendees. Our panel, entitled “Critical perspectives and social theory” allowed us to present our work alongside other critical health scholars. The topics discussed included maternal care (Lianne Holten), dieting (Hilla Nehushtan), community health work (Ryan Logan), and LGBTQ+ mental health (Rachael Eastham).

The use of innovative methods was a recurrent theme throughout the meeting. Presenters made me reflect on all the different ways we can use the internet, for example. Stephanie Lanthier’s (University of Toronto) presentation opened up discussions about using online forums for collecting data, while Carmel Capewell (Oxford Brookes University) talked about some of the limitations of online resources for patients with rare illnesses. I especially appreciated Jenevieve Mannell’s (UCL) presentation and thoughts on qualitative data collection in trial protocols. This discussion highlighted how much we still need to push for the integration of diverse methods into mainstream research. The lack of interest in qualitative methods in the RCT world comes as a result of problematic hierarchical approaches to data. Although qualitative researchers do not dispute the need for RCTs, we also believe there is much more we need to know about health outcomes and the patient experience in order to make informed policy decisions.

Last but not least, the conference symposium introduced us to the use of Story Completion in research – a novel topic for many attendees, including me. Naomi Moller from The Open University walked the audience through the exciting possibilities that such a method offers qualitative researchers. What is Story Completion? you might ask. It is a qualitative research method where participants express their views on topics by finishing a story that was started by the researcher. More specifically, symposium presenters talked about projects where they used Story Completion to collect data. Virginia Braun (The University of Auckland), for example, spoke about using the method in research on healthy eating views, while Toni Williams (Leeds Beckett University) used it to explore narratives of disability and physical activity. Although the method might sound straightforward, presenters made it clear that one must pay careful attention to context, characters, and making sure that the story elicits interest and richness in the participant responses. Story Completion is an exciting method that I will surely consider using in the future.

Needless to say, with such a wealth of information and topics discussed, QHRN 2019 was definitely a great start to our conference season!

2018 has been a busy year for the Remaking the Human Body team. We are happy to share that we have, so far, conducted observations at 5 sites and have interviewed more than 50 professionals and patients about their views on time-lapse, IVF technology, and add-ons in the UK. This year we are looking to finish data collection and are eagerly anticipating the start of our public engagement activities, generously funded by the Wellcome Trust through an additional grant.

By presenting preliminary findings at several conferences, we have incorporated useful feedback from scholars from various academic backgrounds. This, in turn, has helped us hone our questions and methods. We have greatly enjoyed presenting at conferences ranging from science communication meetings to medically-oriented meetings, such as ESHRE. Below is a short list of some of the events we have had the pleasure to attend in 2018, with presentation title in parentheses:

Science in Public 2018 Conference, Cardiff, December 17-19. (Perrotta, M., Geampana, A., Hamper, J.A. “Predicting success: visual practices and predictive algorithms in IVF.”)

European Society for the Study of Science and Technology (EASST) Annual Meeting, Lancaster, July 24-28. (Perrotta, M. & Geampana, A. “Non-invasive predictions: visual predictive tools in IVF.”)

European Society for the Study of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Annual Meeting, Barcelona, July 1-4. (Perrotta, M., Geampana, A., Hamper, J.A., Giraud, AS. “The ethics of commercialization: a temporal analysis of newspaper coverage of IVF add-ons in the UK.”)

Science and Technology Studies Italia Meeting, Padova, June 14-16. (Perrotta, M. & Geampana, A. “Standardising professional vision in embryo imaging.”)

Visualising Reproduction – An Interdisciplinary Inquiry, De Montfort University, Leicester, June 6. (Perrotta, M. “Remaking Embryos. Time-lapse Microscopy and the Future of Embryology.”)

British Sociological Association Human Reproduction Conference, De Montfort University, Leicester, May 24. (Perrotta, M., Geampana, A., Hamper, J.A. “The IVF add-on debate: from techno-scientific breakthroughs to unproven treatments.”)

The previous year has also been a great one to immerse ourselves in the wider world of fertility treatment and education, through attending various public events:

Progress Educational Trust conference ‘Make Do or Amend: Should We Update UK Fertility and Embryo Law? – London, December 5

Fertility Show – London, November 3-4

40 Years of IVF at the Science Museum – London, July 25

Fertility Fest – London, May 8-13

Progress Educational Trust/ British Fertility Society event ‘The Real Cost of IVF’ – London, April 11

Fertility Show – Manchester, March 24-25

In particular, the Fertility Show and Fertility Fest have provided opportunities for us to learn and reflect on how we might proceed with public engagement activities in the near future. You can read some of our previous blogs for impressions from our work and how it fits into wider conversations on fertility and IVF treatment.

We anticipate a productive rest of 2019 and look forward to keeping you posted about our activities!

The annual conference of the Progress Educational Trust (PET), ‘Make Do or Amend: Should We Update UK Fertility and Embryo Law?’ could not have been more timely. Held at the beginning of December, it shortly followed emerging reports from China that the first gene-edited babies will soon be born. While attendees did not miss the opportunity to discuss these developments, the conference provided food for thought for anyone interested in the legal aspects of fertility and reproduction.

The general sense in the room was that the law can hardly keep up with technological developments in this area. As many speakers brilliantly argued, this can lead to problems and frustrations when trying to apply old laws to current contexts. Professor Emily Jackson underlined the issues faced by UK patients as a result of the 10 year legal limit on embryo storage, while Dr Kylie Baldwin highlighted similar issues experienced by women undergoing egg freezing for social reasons. Additionally, the law can be especially restrictive for families who conceive through donation and surrogacy. Both Natalie Gamble and Natalie Smith did an excellent job of underlining changing family practices.

I was especially struck by the diversity that exists within European fertility law. Oftentimes, regulations cannot be separated from the ethical and religious context of their respective countries. This was especially evident in Professor Robert Spaczyński’s presentation on reproductive laws in Poland and Professor Christian de Geyter’s overview of assisted conception in Switzerland. Giving attendees a fascinating picture of the larger European landscape, Satu Rautakallio-Hokkanen, the Chair of Fertility Europe, walked us through many differences between legal restrictions in assisted conception and services offered in various countries across the continent.

For me, a crucial question emerged during the discussion: why is this area of medical practice as regulated as it is? Some have argued that we are talking about procedures that should not even be within the purview of the law. Others might think that we just need better laws, instead of getting rid of them altogether. It is clear, however, that for the time being, fertility and embryo law remains contentious. Consequently, we need to have these debates and conversations in order to find the best solutions. PET’s event made me reflect on bigger questions than the ones I had going in. I had no doubt that better regulations are needed. Now, I wonder, however, about legal systems’ inherent limitations and whether such institutions have the adequate means to cope with rapid changes. Should certain procedures remain unregulated? I have not yet decided on my definitive views, but I’m glad these conversations are happening.

At the beginning of this month, I had the pleasure of attending one of the biggest conferences on reproduction, organized by the European Society for Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE). The ESHRE 2018 annual meeting took place in Barcelona, so, needless to say, I was brimming with excitement not only for the tens of presentations I was going to attend, but also for the amazing location (bonus: the venue was a 10 minute walk from one of Barcelona’s amazing beaches). Sun and beaches aside, the conference was interesting, well organized, and impressive in size and breadth. As a sociologist, I have gotten used to smaller conferences, so I was in for quite the treat: ESHRE had a record attendance this year of almost 12,000! It can be easy to get overwhelmed, but I was there with a purpose: to learn more about the current uses of time-lapse and about social aspects of infertility, more generally.

Time-lapse

Without a doubt, the meeting has confirmed that time-lapse is being used for research in many ways, perhaps more than was initially anticipated by anyone. Time-lapse tools allow embryologists and researchers to study the myriad of factors that can potentially influence pregnancy outcomes. Although add-ons have been portrayed as controversial in the UK media (Most still are: see, for example, recent headlines about the endometrial scratch), it seems to me that time-lapse has nonetheless been integrated into research practices. A number of authors have used time-lapse imaging as data that can generate new knowledge about how to pick the best embryo. We can now look at factors such as fragments, vacuoles, and even type of embryo movement, categorize these phenomena and conduct fairly large studies on outcome correlation, as panels at ESHRE have shown. Of note for me was Dr. Cristina Hickman’s presentation on the multiple uses of time-lapse machines in clinics around the world. Interestingly, she stressed how different labs have integrated this technology to different degrees, showing how introducing new ways of looking at embryos (including selection algorithms) is a process that needs significant work on the part of professionals – work that, however, many say is worth doing in the end. Our own work on time-lapse was represented in the digital poster area, where I was delighted to see many scroll through our summary of preliminary findings.

Fertility Awareness and Men

On top of all the fascinating insights into time-lapse and lab practices, ESHRE 2018 also offered food for thought on fertility awareness, gamete donation, health outcomes for ICSI and IVF children, social egg freezing and many other related topics that I unfortunately have no space to list in a blog post. Taking into consideration the panels I attended and the topics that caught the public’s attention, a couple of prominent themes emerged for me. As infertility is an issue that more and more couples face, the need for fertility awareness education is becoming quite pressing. Presenters and commentators alike noted that this type of education should start early. However, quite a few presentations stressed the absence of men from this conversation. I got a sense that health professionals are worried about this and luckily, researchers are starting to have more conversations with men about reproductive timing and infertility. However, the overwhelming sense was that more work needs to be done to get men involved.

Men’s absence was highlighted in another way: women who undergo social freezing overwhelmingly do so because they haven’t found the right partner. Prof. Marcia Inhorn delved into this subject with data from qualitative interviews conducted in the US and Israel. Interestingly, this is one of the main stories that the media picked up. We are now talking more about men’s lack of a sense of urgency when it comes to having kids. This phenomenon, however, might be problematic in light of increasing knowledge that men also undergo a fertility decline as they age.

To add to all the interesting discussions, I was very glad to see social science perspectives represented at the conference and think we need to start building more bridges with the medical community. This is something that RHB aims for in our future endeavours. We also very much look forward to our next ESHRE meeting!

The early summer conference season has been quite eventful for us. We had the pleasure of presenting some of our initial findings at two events: the British Sociological Association’s (BSA) Human Reproduction Study Group Annual Conference on May 24 and Visualising Reproduction on June 4. Although both took place in Leicester at De Montfort University, they each took a unique and innovative angle on issues emerging in reproduction studies. I here reflect not only on our project’s fit within larger conversations on assisted reproduction, but also on the impressive breadth of topics covered at these two conferences.

Reproduction and the Law

With a very timely choice of topic, the BSA event highlighted critical intersections between reproduction and the law. Coupled with the anticipation of the Irish referendum, I was reminded that the law plays a crucial role in determining our reproductive choices. As someone who has only recently moved to the UK, Professor Emily Jackson’s plenary talk was particularly eye-opening with regards to the legal work that still needs to be done here in order to improve women’s choices. Of course, improvements are necessary everywhere, but the UK has its peculiarities and unique challenges. Most notably, the country has a 10 year storage limit on eggs frozen for social reasons, thus not always allowing women sufficient time to use them to conceive. (An online petition you can sign to change this is in place at https://petition.parliament.uk/petitions/218313) I was also intrigued to find about the various barriers women face as a result of the 1967 Abortion Act. Unquestionably, it is time to change regulations to improve access. Professor Jackson’s talk was an important reminder that we can and should push further.

The presentations I attended throughout the day allowed me to reflect on how we might best regulate gamete donation, surrogacy, and egg freezing, to name just a few topics that came up. The range of global contexts (including North America, Europe and Asia) that presenters explored was impressive and highlighted how ethical challenges are influenced by national policies. In particular, economic inequalities have affected assisted reproduction practices, as governments often fail to keep up with such the changing landscape of assisted reproductive technologies. The regulations required to protect those who are vulnerable, such as surrogates and gamete donors who are based in lower-income countries, are either flawed or non-existent. The BSA event provided a vital space for discussions on how we might proceed. Even though many of us are unsure of the best course of action, starting these conversations is definitely a promising start.

Presenting on Time-lapse

The use of imaging technologies in IVF has been itself caught up in larger debates on commercialisation and best course of treatment. I tried to capture the contentious place that such technologies occupy today in the world of IVF during our presentation at the BSA event. Views on time-lapse have changed tremendously even during the course of our research.

The two conferences we attended perfectly capture the debates/conversations that time-lapse is part of. On one hand, it is a contested technology that potentially calls for more regulatory action in the UK. On the other hand, it captures imaginations with its ability to give us unprecedented insights into the life of embryos. This second aspect brings me to the visual of reproduction and how this was explored during the Visualising Reproduction event.

Visualising Reproduction

With topics ranging from the history of embryo illustrations to menstruation in the visual arts to holographic visualisations of the clitoris, Visualizing Reproduction was fascinating, unique, and much-needed conference that showcased the significance of reproductive imagery. Listening to the invited speakers (including our very own Manuela Perrotta), I realised that many topics we study in the social sciences are intricately related to art and visualisation. In particular, the conference highlighted collaborations between artists and academics. This stood out me as interdisciplinarity at its best. For example, Isabel Davis from Birkbeck and artist Anna Burel talked about the Experimental Conception Hospital imagined by Robert Lyall, a 19th century physician. Anna’s illustrations of pregnant women and art pieces made Lyall’s imagined institution come to life. Another example of amazing work from artists was Liv Pennington’s exploration of pregnancy tests – a technology so mundane yet at the same time so mysterious. Thinking about such work, it strikes me that the visual has the power to break down taboos and barriers, as also exemplified in representations of menstruation in the arts – a topic that Camilla Røstvik brilliantly covered in her presentation.

Visual Representations has taught us that fruitful collaborations between artists and academics might be able to provide a better-rounded picture of the topic studied. It has also taught us that we need to further emphasize the visual in our project’s exploration of time-lapse and its uses.